Solved: Mystery of phantom limb pain

By Andrew Tobin | May 28, 2014 | Haaretz

An Israeli-led team of scientists has located and blocked the often-painful sensation that a phantom limb is lurking in place of an amputated one.

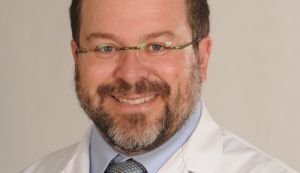

Dr. Haim-Moshe Adahan ran the Israeli trial at Chaim Sheba Medical Center at Tel Hashomer.

"Phantom limbs" have long been a mystery. Early theories saw them as proof of the immortal soul or part of the Freudian mourning process for the amputated limb. Nowadays, the standard explanation is that the ghostly appendages - which lurk painfully in place of amputated ones - result from confusion in the brain's map of the body.

In a new study, Israeli and Albanian researchers have found the primary source of phantom limb syndrome in nerves near the spine - and managed to alleviate the associated pain. Their work proves that phantom limbs are not "imagined" in the brain, but "felt" in the body. A version of the procedure used in the study, which is to be published in the journal Pain in May, could soon improve quality of life for millions of amputees.

"In a way, the debate about the origin of phantom limb syndrome is a version of the ancient mind-body problem," said professor Marshall Devor of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem's Department of Cell and Developmental Biology and Center for Research on Pain, who led the study. "Our research resolves the problem, at least in this case. It's the body."

The ghost in the machine

Limbs have been getting lopped and blown off - whether from war, mishap or surgery - since antiquity, with some people always managing to survive. Ancient Egyptian mummies have been unearthed wearing prosthetics; and Roman general Marcus Sergius switched to fighting the Second Punic War left-handed after losing his right one (and replacing it with an iron prosthetic in the style of fictional knight Jaime Lannister of HBO series "Game of Thrones").

There are an estimated 10 million amputees in the world. Pretty much all of them experience phantom limb syndrome - the perception of sensations in a limb that has been amputated - and up to 80 percent suffer from pain in the limb. Phantom limb pain, which can be shooting, stabbing, burning or electric shock-like, usually eases in frequency and intensity over time - but may never go away.

Skeptical of conventional brain-centric explanations of phantom limb syndrome, Devor and his colleagues set out to test another neurobiological theory: that phantom limb syndrome comes from the nerve fibers that used to run to the amputated limb. Guided by medical imaging, the researchers injected 31 leg amputees who suffered from phantom limb syndrome - 16 in Albania and 15 in Israel - with local anesthetic near where the nerves from their amputated legs enter the spinal cord in the lower back.

Within minutes, phantom limb sensation and pain was temporarily reduced or eliminated in all the amputees. Control injections had no effect; nor did numbing nerves in the stump in the few cases tested.

Body over mind

The results of the study establish that phantom limb syndrome primarily comes from the nervous system at or below the spine. If the sensations were coming from the brain, the injections would have had no effect. The most likely culprit is the dorsal root ganglion, a cluster of neurons that carries signals from the body to the spinal cord, from where they are transmitted to the brain.

The researchers say these neurons, which were the target of the study, probably begin terrorizing the brain with abnormal signals when the limb they innervate is amputated, causing the pain and other sensations characteristic of phantom limb syndrome. The anesthetic appears to block signals associated with the phantom limbs from reaching the brain.

As the ultimate organ of sensory perception, the brain plays a role in phantom limb syndrome, and may even originate some of the symptoms. For instance, the common sensation that a phantom limb is withdrawing, or "telescoping," into the stump over time may be due to maladaptive plasticity - the shrinking of an area of the primary somatosensory cortex that once sensed the real limb. Where most scientists were wrong, it turns out, was in thinking this theory explains phantom limb syndrome and pain entirely.

"The dismantling of phantoms via the silencing of these terror cells' is in my mind a death blow to the brain theory of phantom pain and a call to industry to join forces with scientists to find new treatments for neuropathic pain," said Dr. Haim-Moshe Adahan, who ran the Israeli trial at Chaim Sheba Medical Center at Tel Hashomer's Pain Rehabilitation Unit and is working on a follow-up study to extend symptom relief using steroids.

Amputees have come so far that a sprinter who lost both his legs qualified for the last summer Olympics, Adahan notes. What hasn't improved significantly is treatment for phantom limb pain, which he says continues to haunt Israeli soldiers and other amputees he treats. Thanks to the study, doctors may for the first time in thousands of year be able to "amputate" phantom limbs, offering relief to many millions.